- Home

- John Bunyan

The Pilgrim's Progress Page 2

The Pilgrim's Progress Read online

Page 2

This fine early story’s concern with the ordered and the disordered prefigures many other instances later in Buchan’s literary career. In ‘Fountainblue’ (1901), collected here, the Cabinet minister Maitland talks of the ‘very narrow line between the warm room and the savage out-of-doors… You call it miles of rampart; I call the division a line, a thread, a sheet of glass.’ The same sentiment is expressed in Buchan’s novel The Power House (1916): ‘You think that a wall as solid as the earth separates civilisation from barbarism. I tell you the division is a thread, a sheet of glass. A touch here, a push there, and you bring back the reign of Saturn.’

Buchan often in fact actively seems to be trying to do just that in these tales. Like his novels, they derive much of their power from flirtation with sin, the underworld or the occult. In one story he raises the devil directly. ‘A Journey of Little Profit’, also in The Yellow Book in 1896, tells the story of a young drover who does not sup with a long enough spoon. The lack of mastery over one’s own passions identified in the shepherd seems to be linked in Buchan’s mind with the eternal struggle between good and evil.

In Buchan’s world-view, only the strongest men can contain that struggle, which is signified throughout his work by a religiously inflected dialectic between mastery and weakness. Mastery over one’s own sensuality usually means the fulfilment of one’s destiny and some great role in life. So the Salvation Captain has ‘almost the power’ of being a great leader, ‘for in his masterful brow and firm mouth there were hints of extraordinary strength’. One of his companions, meanwhile, who does not have this strength, is depicted as having ‘flopped on his knees beside the sofa and poured forth entreaties to his Master’.

As President of the Scottish History Society in later life, Buchan played a big role in preserving collections of folkloric records. In these stories we see him playing a similar kind of curatorial role. It is part of Buchan’s genius to link the observed patterns of agricultural life under stress from industry and social change to a mythic past in which materialism played no role.

This is strongly evident in the story ‘Streams of Water in the South’ (1896). One of my own favourites, it may be that it was also one of the author’s own since it is among the few stories to be included in both of his main short-story collections Grey Weather (1899) and The Moon Endureth (1912). As Lownie has pointed out, ‘It exhibits certain parallels with Walter Scott’s “Wandering Willie’s Tale”.’ In his stories Buchan consciously imitated not just Scott but also R. L. Stevenson. He also, in a slightly different mode, paid homage to Joseph Conrad and Rudyard Kipling.

‘Streams of Water in the South’ is narrated part by a young man who seems close to Buchan himself, part by the shepherd Jock Rorison. The main character is Streams o’ Water or Yeddie or Adam Logan, as he is variously known. Streams o’ Water is a strange figure who appears out of nowhere in the Border hills to help drovers herding their sheep through torrential burns. He does so out of a mixture of pure generosity and a compulsion which is destinal or even curse-like.

The harshly realist ending is in sharp contrast to what we first hear about Streams o’ Water. It begins in a ‘romantic narration’ of Rorison’s which is listened to and described by the young Buchan figure. Then, ‘the strange figure wrestling in the brown stream took fast hold on my mind, and I asked the shepherd for further tales.’ By the time Yeddie appears again, he moves like a wraith between actuality, story and legend:

So the shepherd talked, and as at evening we stood by his door we saw a figure moving into the gathering shadows. I knew it at once and did not need my friend’s ‘There gangs “Streams o’ Water”’ to recognise it. Something wild and pathetic in the old man’s face haunted me like a dream, and as the dusk swallowed him up, he seemed like some old Druid recalled of the gods to his ancient habitation of the moors.

Ancient habitations also feature in ‘The Watcher by the Threshold’ (1900), the title story of another collection of Buchan stories, published in 1902. Ladlaw, ‘a cheery, good-humoured fellow, a great sportsman,’ is transformed when believing himself possessed by the spirit of the surrounding moor, apparently the holy land of the ancient Picts. Ladlaw also exemplifies another common concern of many of these stories, which is the man who suffers a change in his life.

Sometimes it can be a happy change. In ‘“Divus” Johnston’ (1913), a sailor from the Glasgow suburbs finds himself being worshipped as a god somewhere in south-east Asia. But more usually the change is a sad one involving a sacrifice of some type. In ‘Fountainblue’, for example, the politician disappointed in love, Maitland, ‘saw our indoor civilisation and his own destiny in so sharp a contrast that he could not choose but make the severance’. He throws off his glittering political career to go to Africa.

The special house or garden or other type of place is another preoccupation of Buchan’s. In Scottish legend it might be a fairy glen. In his autobiography, Buchan himself described it as the sacred grove of the Greeks, ‘a temenos, a place enchanted and consecrate’. One of its most powerful showings is in the story ‘The Grove of Ashtaroth’ (1910), in which the main character worships an ancient goddess in his garden.

The same idea is at work in ‘The Wind in the Portico’ (1928), in which a man builds a temple for Vaunus, a British god of the hills, who then takes revenge by burning his votary for trying to change the dedication of the temple. We also see the special place in ‘Basilissa’, ‘The Watcher by the Threshold’ and ‘Fountainblue’.

Once again in the last-named there is a sense of an anti-materialist primitive remnant continuing to exert its power over the centuries: ‘Fountainblue – the name rang witchingly in his ears. Fountainblue, the last home of the Good Folk, the last hold of the vanished kings, where the last wolf in Scotland was slain, and, as stories go, the last saint of the Great Ages taught the people – what had Fountain-blue to do with his hard world of facts and figures?’

The themes of the special place and transformation of individuals come together most powerfully in ‘Fullcircle’ (1920), in which visitors to a house in the Midlands see it and its owners, the Giffens, become subject to successive changes. The story comes from house-hunting trips Buchan made with Susan in the Cotswolds in 1917 while looking for Elsfield. Loosely based on Sidney and Beatrice Webb, the Giffens start as psychologising socialists ‘in revolt against everything and everybody with any ancestry’. They end, via a period as hunting and fishing members of squirearchy, as austere yet strangely sensual Catholics. The house, which contains a small chapel and was built by a Catholic aristocrat after the Restoration, has come ‘full circle’. As the fascinated and part frightened narrator puts it, ‘Some agency had been at work here, some agency other and more potent than the process of time.’

In ‘The Loathly Opposite’ (1927), the agency at work is a code-writer on the opposing German side in the First World War. Fans of Robert Harris’s Enigma and those interested in the work at Bletchley Park in the subsequent war will be amused by how the cypher is broken. But as Lownie has pointed out, perhaps the real coup of the story is how it links decypheration with ‘cracking the code’ of the human mind.

‘Ship to Tarshish’ (1927) is one of Buchan’s most technically well-achieved stories. It may not have the outlandish elements we find in others, but its narrative of Jim Hallward, a man who flees England to Canada out of ‘funk’ after a financial crisis, then comes back – then goes again, this time out of courage – encapsulates many of Buchan’s themes, in particular that of finding redemption through hard work.

‘Ship to Tarshish’ bears interesting comparison with some of the other stories in this volume. In ‘A Captain of Salvation’ the change in life is one way, though there are temptations to reverse it; in’ “Divus” Johnston’, the change is reversed, but Johnston comes back from the East a much richer man. In Hallward’s case the change is reversed and turned about once again, and the riches are those of the spirit.

For sheer effect, the most powerful

story in this volume is ‘Tendebant Manus’ (1927). This story of spiritual companionship between brothers after one of them has died is extraordinarily convincing. Partly it is the setting that does this, the wonderful duck-shooting scene in which the principal revelation is made. But the main reason for the effectiveness of the story is the way the magic of it is not determined by some external power but by the actual workings of the human mind. Anyone who has ever been bereaved will appreciate its power.

Both first published in Pall Mall Magazine in 1928, ‘The Last Crusade’ and ‘Sing a Song of Sixpence’ are also very effective. One a story of the emergent media industry owing something to Buchan’s time at Reuters, the other a strangely toned, much anthologised tale of terrorism told by Leithen himself, they are expressly concerned with the impact of modernity. In terms of content, they look back to Joseph Conrad’s political short stories of the 1890s and forward not just to the thriller-writers of today but also to more avant-garde authors.

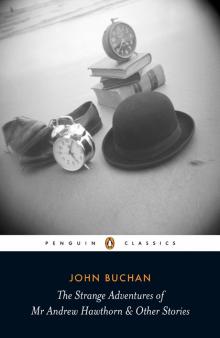

The last story in this volume, ‘The Strange Adventures of Mr Andrew Hawthorn’ (1932), is in many ways the comic counterpoint of ‘Ship to Tarshish’. Another story about a man who dips out of life, it begins with a kind of explanation of the allure of this trope:

Any disappearance is a romantic thing, especially if it be unexpected and inexplicable. To vanish from the common world and leave no trace, and to return with the same suddenness and mystery, satisfies the eternal human sense of wonder. That is why the old stories make so much of it. Tamlane and Kilmeny and Ogier the Dane retired to Fairy Land, and Oisin to the Land of the Ever Living, and no man knows the manner of their going or their return. The common world goes on, but they are far away in a magic universe of their own.

It is Buchan’s ability to transport his readers to this magic universe which has produced so many devotees of his writing. I think he actively believed in that universe and for all his best efforts as a good Presbyterian could not stop his own mental recursion to the pagan.

In ‘Space’ (1910), which proceeds from his reading of the French physicist Henri Poincaré, he even tries to find a scientific basis for that recursion: ‘How if Space is really full of things we cannot see and as yet do not know?’ This tale of a doomed scientist told by Leithen to an unnamed narrator ends with the latter seeking refuge in solid, evidence-based reality:

We were now on the gravel of the drive, and I was feeling better. The thought of dinner warmed my heart and drove out the eeriness of the twilight glen. The hour between dog and wolf was passing. After all, there was a gross and jolly earth at hand for wise men who had a mind to comfort.

Leithen, however, fixes on ‘the land of pure spirit’. The two positions are held in balance in Buchan’s stories. One only needs begin reading them to be either taken into a separate world of the imagination or returned with a necessary bump to harsh physical reality. Many writers perform one or other of these services. Few are capable of doing both. Even rarer are those who, like John Buchan, can do both at the same time.

GILES FODEN

A Captain of Salvation

Nor is it any matter of sorrow to us that the gods of the Pagans are no more. For whatsoever virtue was theirs is embodied in our most blessed faith. For whereas Apollo was the most noble of men in appearance and seemed to his devotees the incarnation (if I may use so sacred a word in a profane sense) of the beauty of the male, we have learned to apprehend a higher beauty of the Spirit, as in our blessed Saints. And whereas Jupiter was the king of the world, we have another and more excellent King, even God the Father, the Holy Trinity. And whereas Mars was the god of war, the strongest and most warlike of beings, we have the great soldier of our cause, even the Captain of our Salvation. And whereas the most lovely of women was Venus, beautiful alike in spirit and body, to wit our Blessed Lady. So it is seen that whatever delights are carnal and of the flesh, such are met by greater delights of Christ and His Church.

An Extract from tine, writings of Donisarius, a Monk of Padua

The Salvation Captain sat in his room at the close of a windy March day. It had been a time of storm and sun, blustering showers and flying scuds of wind. The spring was at the threshold with its unrest and promise; it was the season of turmoil and disquietude in Nature, and turmoil and disquietude in those whose ears are open to her piping. Even there, in a three-pair back, in the odoriferous lands of Limehouse, the spring penetrated with scarcely diminished vigour. Dust had been whistling in the narrow streets; the leaden sky, filled with vanishing spaces of blue, had made the dull brick seem doubly sordid; and the sudden fresh gusts had caused the heavy sickening smells of stale food and unwholesome lodging to seem by contrast more hateful than words.

The Captain was a man of some forty years, tall, with a face deeply marked with weather and evil living. An air of super-induced gravity served only to accentuate the original. His countenance was a sort of epitome of life, full of traces of passion and nobler impulse, with now and then a shadow of refinement and a passing glimpse of breeding. His history had been of that kind which we would call striking, were it not so common. A gentleman born, a scholar after a fashion, with a full experience of the better side of civilisation, he had begun life as well as one can nowadays. For some time things had gone well; then came the utter and irretrievable ruin. A temptation which meets many men in their career met him, and he was overthrown. His name disappeared from the books of his clubs, people spoke of him in a whisper, his friends were crushed with shame. As for the man himself, he took it otherwise. He simply went under, disappeared from the ranks of life into the seething, struggling, disordered crowd below. He, if anything, rather enjoyed the change, for there was in him something of that brutality which is a necessary part of the natures of great leaders of men and great scoundrels. The accidents of his environment had made him the latter; he had almost the power of proving the former, for in his masterful brow and firm mouth there were hints of extraordinary strength. His history after his downfall was as picturesque a record as needs be. Years of wandering and fighting, sin and cruelty, generosity and meanness followed. There were few trades and few parts of the earth in which he had not tried his luck. Then there had come a violent change. Somewhere on the face of the globe he had met a man and heard words; and the direction of his life veered round of a sudden to the opposite. Culture, family ties, social bonds had been of no avail to wean him from his headstrong impulses. An ignorant man, speaking plainly some strong sentences which are unintelligible to three-fourths of the world, had worked the change; and spring found him already two years a servant in that body of men and women who had first sought to teach him the way of life.

These two years had been years of struggle, which only a man who has lived such a life can hope to enter upon. A nature which has run riot for two decades is not cabined and confined at a moment’s notice. He had been a wanderer like Cain, and the very dwelling in houses had its hardships for him. But in this matter even his former vice came to aid him. He had been proud and self-willed before in his conflict with virtue. He would be proud and self-willed now in his fight with evil. To his comrades and to himself he said that only the grace of God kept him from wrong; in his inmost heart he felt that the grace of God was only an elegant name for his own pride of will.

As he sat now in that unlovely place, he felt sick of his surroundings and unnaturally restive. The day had been a trying one for him. In the morning he had gone West on some money-collecting errand, one which his soul loathed, performed only as an exercise in resignation. It was a bitter experience for him to pass along Piccadilly in his shabby uniform, the badge in the eyes of most people of half-crazy weakness. He had passed restaurants and eating-houses, and his hunger had pained him, for at home he lived on the barest. He had seen crowds of well-dressed men and women, some of whom he dimly recognised, who had no time even to glance at the insignificant wayfarer. Old ungodly longings after luxury had come to disturb him. He had striven to banish them from his mind, and had muttered to himself many

texts of Scripture and spoken many catchword prayers, for the fiend was hard to exorcise.

The afternoon had been something worse, for he had been deputed to go to a little meeting in Poplar, a gathering of factory-girls and mechanics who met there to talk of the furtherance of Christ’s kingdom. On his way the spirit of spring had been at work in him. The whistling of the wind among the crazy chimneys, the occasional sharp gust from the river, the strong smell of a tan-yard, even the rough working-dress of the men he passed, recalled to him the roughness and vigour of his old life. In the forenoon his memories had been of the fashion and luxury of his youth; in the afternoon they were of his world-wide wanderings, their hardships and delights. When he came to the stuffy upper room where the meeting was held, his state of mind was far from the meek resignation which he sought to cultivate. A sort of angry unrest held him, which he struggled with till his whole nature was in a ferment. The meeting did not tend to soothe him. Brother followed sister in aimless remarks, seething with false sentiment and sickly enthusiasm, till the strong man was near to disgust. The things which he thought he loved most dearly, of a sudden became loathsome. The hysterical fervours of the girls, which only yesterday he would have been ready to call ‘love for the Lord’, seemed now perilously near absurdity. The loud ‘Amens’ and ‘Hallelujahs’ of the men jarred, not on his good taste (that had long gone under), but on his sense of the ludicrous. He found himself more than once admitting the unregenerate thought, ‘What wretched nonsense is this? When men are living and dying, fighting and making love all around, when the glorious earth is calling with a hundred voices, what fools and children they are to babble in this way!’ But this ordeal went by. He was able to make some conventional remarks at the end, which his hearers treasured as ‘precious and true’, and he left the place with the shamefaced feeling that for the first time in his new life he had acted a part.

The Pilgrim's Progress

The Pilgrim's Progress